Message to the Faithful

If I knew how to fix things, I would. But I'm not a guru. I'm not about to start a new denomination. Here's where I call on the leaders of our traditional faiths to do what I can't.

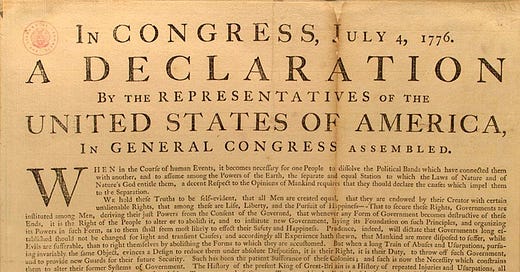

The American Spirit Essays #42

Previous: Making My Case

Still Not a Guru

This part of the story is where it becomes relevant that I’m not a wannabe guru: The final part. So I’ll repeat it: I’m not a wannabe guru. I am, however, a professional troubleshooter, problem-solver, and strategist. Which is fortunate, because American society is in serious trouble, facing deep problems, and in dire need of a strategy to right itself before it’s too late.

Throughout this essay series, I’ve tried to tell the stories of America’s spiritual crisis, the American Spirit, and the Great Awokening in a way that builds towards a solution. Not that any of these steps are simple, but we’ve got to do three things:

1. Find messages in traditional faiths to address the spiritual crisis.

2. Reinvigorate the American Spirit.

3. Treat Wokeism like the religion it is.

The first task is largely out of my purview precisely because I don’t want to become a guru or found my own denomination. I am not a fan of the many Jewish and Christian denominations of which I am aware (and their counterparts in other faiths of which I am less aware) that simply reinvent their faith’s beliefs, practices, and traditions to suit the taste of today’s parishioners.

Jewish and American

As a Jew, I take deep offense at the Jewish organizations and clergy that have untethered Judaism from its rich past. Judaism places at its center the unity of God, the nation of Israel, and the eternal covenant linking them together. To Jews, the Torah’s designation of our nation as a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” has essentially set us up as a demonstration project.

Our adherence to God’s covenant is supposed to set a model for the rest of the world to follow. Judaism doesn’t simply morph into whatever it is that enough Jews believe. The land of Israel and the keeping of the Sabbath play enormously important roles in defining the community. Jewish laws and rituals have remained largely unchanged for millennia. Jewish positions on controversial topics like abortion, euthanasia, and sexuality were formed long ago—and they do not align with those of Wokeism. Jewish positions on the environment, taxes, welfare, warfare, and countless other matters of contemporary politics are far more flexible; Woke perspectives may be consistent with Jewish views, but then so too are most non-Woke views. The contemporary reduction of Judaism to a bland ethical command to “fix the world” (tikkun olam) in a manner that coincidentally aligns perfectly with Wokeism is both offensive and anti-Jewish.

As an American whose personal level of religious observance has varied widely throughout his life, I remain a believer in free will and free choice. I find the notion of enforced observance at least as offensive as the notion of amorphous traditionalism. But an individual choice to transgress one or more religious rules can do nothing to alter the tradition—or the viability of the rules. So too with an individual choice to support politicians and policies that run counter to traditional teachings, ethics, or practices.

Judaism is what it is, regardless of what any number of today’s Jews may want it to be. There may be some red lines—in life choices or political choices—that make an individual, even an individual Jew, anti-Jewish (in fact, there almost certainly are such red lines). But traditionalists must take pains to ensure that such lines are both few and clear. Moreover, they must be clear that such lines exist not because they run against the Jewish practice of the individual but rather because they threaten to undermine the continued existence or safety of the Jewish people, of Jews to live as Jews.

Beyond that, by all means, let people know when Judaism expects something of them. If they choose to live, act, or vote differently—well, that’s the American spirit in action. It’s also, however, the American component of American Judaism that has allowed Judaism and Jews to thrive in America. No one ever promised that every traditional interpretation of every faith could thrive in America. Religious traditionalists of all stripes were invited to find, define, or tailor versions of their traditions to American soil. That task was always going to be easier for some than for others. The invitation remains as it was. I’ve written these essays in part as a call to America’s traditional faith leaders to remember that invitation and its terms, to look in the mirror, and to see what needs to be done to accept it within contemporary American sociological context.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to American Restoration by Bruce D. Abramson to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.