The Separation that Defined America: Christian Exceptionalism

The separation of church and state is a radical idea. Even more radical is the idea that religion is separable from life in general. Only some quirks of European history made it possible.

The American Spirit Essays #11

(Previous: Something New Under the Sun)

More Uniqueness

This essay continues our consideration of America’s debilitating spiritual crisis. It builds upon the previous essay’s recognition that our shift from a world of scarcity to a world of abundance has altered the human relationship with God.

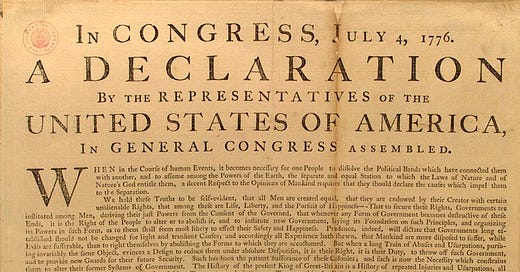

The downgrading and abandonment of the provider/protector deity so central to so many of the world’s faith traditions is only part of the story. Another important element lies in the separation of church and state—a division so natural and so central to the American identity that we enshrined it in the Bill of Rights.

Few contemporary Americans have ever stopped to consider just how bizarre and unique that separation is. Historically speaking, only minority religions ever favored such a separation. “Maybe if we pay our taxes and fly the flag, the King will let us practice our faith in peace” is the sort of thing uttered exclusively by adherents of faiths other than the King’s. The relegation of religion to a distinctive set of prayers, rituals, and holidays—effectively reserving large swathes of economic and social life to the state or to the people—is a rather recent and very Western innovation. In trying to understand the spiritual crisis undermining American life today, it’s worth taking a bit of a detour to consider the origins of this very American anomaly.

In the parts of the world long dominated by Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism—as well as what we know about Pre-Columbian Americas and the pagan worlds that preceded Christianity and Islam—no such distinction has ever existed. In some times and places the official religion has been subservient to the state; in others, the state has served the faith. In almost no historical context other than our own has there been a division among clerical, temporal, cultural, and economic spheres sufficiently clean for those controlling one part of society to disregard the concerns and traditions inherent in the others. Even today, in the Muslim-majority world, Islam is far more a way of life than a distinctive set of holidays and prayer texts. The same it true in selected small Jewish enclaves and among groups like the Amish.

The lines among faith, culture, and governance have always been blurred. In biblical Judaism, leaders from Moses through the Judges to the Kings were handed rights and responsibilities, by God, through priests and prophets. When King Saul failed to follow a direct command to the letter, God told Samuel to wrest the royal line from him and hand it to David. Most of the later prophets spent most of their time admonishing the Kings of Judah and Israel—not for failed governance or flawed economics, but for deviating from God’s word. Jews did not develop the edict of dina d’malchuta dina—the law of the land is the law—until the Roman decimation of Judea in the wake of the Bar Kochba rebellion. Only with that concept in place could Jews then comfortably obey temporal laws that differed from the prescribed Jewish lifestyle (with only a small subset carved out as exceptions).

The European Anomaly

Of all the world’s great faiths, Christianity has taken by far the most interesting and unusual trek down this path. It’s noteworthy that—according to all three synoptic gospels—the people who heard Jesus proclaim: “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s; render unto God what is God’s” “marveled” at its wisdom.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to American Restoration by Bruce D. Abramson to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.